Attack of the Safe Starches

If you have been lurking around paleoland recently you will have heard the debate about safe starches (you may be sick of hearing about it in fact). Last fall I ran an experiment to find out whether it might be a good idea to dip my toe into the safe starch swimming pool. I was tracking my lipids around this time with the CardioChek PA so I could have some idea of what was going on with my metabolism. Here are the results.

I first experimented with a low carbohydrate diet in 2009 after reading Good Calories, Bad Calories by Gary Taubes. I lost 15 pounds in the first three months (though I had no idea I was carrying any extra fat). I gained muscle without changing my exercise program. My seasonal allergies went away. My teeth got whiter, less sensitive and stopped collecting plaque. I got fewer sunburns. My joints stopped aching after exercise. You get the idea.

Around this time I took an oral glucose tolerance test and found my numbers to be a bit high, though not in the pre-diabetic range just yet. I tend to get a high initial blood sugar spike, though the value quickly returns to normal. I thought this (along with the other general health improvements I experienced) was an indicator that a low carb diet was a good approach for me. I bought a cheap glucometer to play with and stuck with the low carb program.

Over the years my diet progressed to a paleo approach, while I continued to avoid starches. On most days I ate only eggs, meat, fish, some nuts and a good helping of green veggies. Given the safe starches controversy, I thought it would be interesting to try adding 100g or so of carbs per day in the form of sweet potatoes, just to see what would happen. There is a variety of chatter about the possibility that low carbohydrate diets can raise LDL, so I thought I might see a drop in non-HDL cholesterol with a bit of added starches. I did get a drop, but it wasn't to the non-HDL.

Results

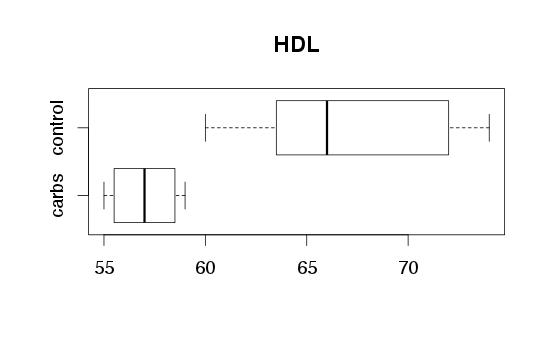

Mean non-HDL did not change during the experiment (193 to 203, not statistically significant), but mean HDL dropped by a significant amount (67 to 57, p<0.001). I stopped the experiment after one month. You'll see in the plot below that the HDL went back up to the previous level after the daily sweet potato was dropped.

|

| Boxplots show minimum, maximum and quintiles. Mean HDL: 67 (control), 57 (carbs). |

|

| The trendline is a linear model based on all low carb data points (before and after, but not including, the carb intervention). |

|

| Trendline based on all low-carb points. Non-HDL cholesterol was not significantly affected. |

Details of the Experiment

The data points were collected as previously discussed in the butter experiment. Data does not include any points during the butter experiment, as there was a significant change in HDL and non-HDL during that time. Statistical significance test is based on a linear model, calculated by ANOVA using R.Sweet potatoes were eaten slowly so as not to spike blood sugar above 120, though spikes may have occurred on occasion. It usually takes me about an hour to eat one, though I can eat them very fast without a spike if I've recently completed a heavy workout.

There are a number of limitations to the interpretation of this data that are worth mentioning. Perhaps most significantly, this is a very short term test (1 month). It is possible that long term adaptations would have reversed the effects seen here. Second, there was only a single intervention period, which could have corresponded to another unknown variable which caused HDL to decrease. Since foods differ in micronutrient, mineral and toxin content, it is not possible to generalize from sweet potatoes to all carbohydrates. I may have had a different result with white rice, white potatoes, taro, tapioca, etc. Finally, of course this result applies to me only. There may be others who have a much higher carbohydrate tolerance, or who may even see the opposite result.

Is This Actionable Information?

So why am I bothering with this? First of all, simple curiosity. I have the ability to collect data that most people do not collect, and there is some interesting science concerning these molecules and what they may be able to tell me about my metabolism.

Does the decrease in HDL identified here represent an unhealthy change? Perhaps. Though HDL is commonly referred to as the "good cholesterol", I would not suggest that all decreases in HDL are unhealthy. In fact I don't know how one would go about establishing the truth or falsehood of a statement like that. Conversely, we know of chemicals that raise HDL while simultaneously causing heart attacks. My HDL was never "low" during the course of this experiment. However, together with certain other data I was also collecting at this time (which is a story for another day), I believe that 100 grams of starch per day is too much for me. At least in my current metabolic state, with my current lifestyle, exercise habits, sleep, stress level, etc.

Some smaller amount of starch is most likely "safe," and may be a good idea. These days I often eat a banana (about 20-30 grams of sugar+starch) after lunch, and I have not seen the negative effects caused in me by higher amounts of carbohydrate. As mentioned, I also have found that I can eat 100 grams of carbs immediately after a heavy workout with no significant change in my blood sugar (e.g. it might increase from 65 to 83 in response to a pound of sweet potatoes after two hours of powerlifting). These days, workouts like that occur about once a week (sometimes less), and I have not noticed any negative effects from eating carbs this infrequently. Since many smart (and strong) people advocate carbs post-workout, I am willing to go along for now, at least while I do not have any contradictory evidence.

Published Research

Perhaps if I had looked this stuff up in the scientific literature first I would have been less surprised by my results. It turns out there is plenty of published research supporting the idea that carbs lower HDL. However, it is a bit surprising that the relationship continues even below 100g/day. I doubt there is published research on this relevant to long-term low carbers, so three cheers for personal science on that front. A study by a German team, published in January 2012 in the Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, does a good job summing up the research that is out there. Here is their conclusion regarding carbohydrates and HDL:

"There is convincing evidence that a higher carbohydrate proportion in the diet at the expense of total fat or saturated fatty acids intake lowers the plasma concentration of HDL cholesterol."

The paper is called "Evidence-Based Guideline of the German Nutrition Society: Carbohydrate Intake and Prevention of Nutrition-Related Disease." It is worth a read if you are interested and still awake. If instead you are sleeping (and not German), perhaps you are dreaming of a world in which the nutrition organizations in your country also use evidence as the basis for their guidelines.

Nicely done!

ReplyDelete"The present evidence-based guideline regarding carbohydrate intake and primary prevention of the diseases considered here has shown that the quality rather than the quantity of carbohydrate intake is important for the primary prevention of nutrition-related diseases."

ReplyDeleteGreat.

"The total intake of dietary fibre and especially the intake of whole-grain products, which are foods high in dietary fibre, should be increased, as this reduces the risk of various nutritionrelated diseases."

Ahh, almost ...

:-(

Fruit it seems doesn't have this effect:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.ajcn.org/content/72/5/1095.short

Thanks for the link. There clearly are many differences between fruit and sweet potatoes, and I wouldn't expect my results necessarily to translate to fruit. However, I did not find the study you linked (on orange juice vs. blood lipids over a 17 week intervention) especially convincing.

DeleteFirst of all, you'll notice that my HDL dropped during my experimental period (when I added the additional sweet potato per day) but was quickly restored to baseline levels within a week of stopping. In the study you referenced, HDL increased during the intervention, and then increased further in the washout period, even though orange juice consumption had dropped substantially. This is consistent with the idea that the dietary intervention alone (a low-fat AHA diet, which was followed throughout the entire study including the washout period) was the cause of the rise in HDL. Since the study was run without a control group, we also can't decide whether the HDL increased as a placebo effect from participating in the study. The authors speculate about a persistent effect of the plant flavonones in citrus, but if they knew about that from their prior in vitro work, they should have designed in a longer washout period.

In my test I just about tripled my carbohydrate intake (from a ketogenic baseline) with primarily glucose from sweet potatoes. The participants in this study added on average about 50 grams of carbs (net) mostly in the form of fructose to an already high carbohydrate diet. I substituted protein and fat for my carbs, because my appetite decreased (baked sweet potatoes with coconut butter and cinnamon are delicious and very satiating). The participants in this study did not substitute anything for the added orange juice -- they just ate more total calories. So I guess we can infer that orange juice is not satiating. The participants' calorie intake spontaneously went down during the washout period. In fact, their food intake dropped by more (in calorie units) than their orange juice consumption, meaning that they not only dropped the orange juice but also ate a bit less of everything else!

The designers of the orange juice study changed everyone's duet to a low fat diet, and also took nearly a quarter of them off of lipid lowering drugs. Since we are not shown data points for individual participants we can't see if the drug cesassion skewed the statistics overall.

One thing that did seem to correlate with the orange juice intervention was fasting triglycerides, which went up as a result of the intervention and returned to baseline in the washout. This is not unexpected given an increase in high glycemic carbohydrates. The only other measured quantities that behaved this way were folate and vitamin C, which the authors were using as markers of orange juice consumption.

The authors were expecting to see a decrease in LDL (based on hypercholesterolemic rabbit studies and in vitro cell culture work) and a decrease in homocysteine (from the folate). Neither of these things happened.

Overall, we can't really tell from this study whether orange juice raises HDL, though it does appear to raise triglycerides, which would normally be associated with a drop in HDL, so that finding is interesting in that respect. The authors speculate a role for citrus flavonoids and not the orange juice carbohydrates. Some of these are known to bind estrogen receptors, so we are back to plant hormones. I am somewhat skeptical of the idea that specific exegenous hormones from food are necessary for optimal health. It is hard to align that concept with an evolutionary perspective given the high level of variability in ancestral diets. That said, I am preparing a post on a different exogenous hormone (which does not come from food) that does appear to be necessary for optimal health!

I currently have xanthelasmas under my eyes that appeared after I reintroduced 100g carbs per day, and doing some research xanthelasmas are associated with low HDL levels http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2717981

ReplyDeleteGoing to go back to VLC asap!